Introduction: The Cornerstone of Checks and Balances

The structure of the United States government is built upon a foundational principle: no single branch should wield unchecked authority. To preserve this balance, the Constitution established a system of checks and balances, ensuring each branch—legislative, executive, and judicial—can limit the powers of the others. Among these safeguards, the judiciary plays a pivotal role in monitoring congressional action. The most powerful tool at its disposal is judicial review, the authority to assess whether laws passed by Congress align with the U.S. Constitution. When a law is found to violate constitutional principles, the courts have the power to invalidate it. This mechanism not only reinforces the rule of law but also protects individual rights and maintains the structural integrity of American democracy. This article explores how judicial review functions, where it originated, and why it remains essential to the nation’s governance.

What is Judicial Review? Defining the Core Power

At its core, judicial review grants federal courts the authority to examine laws, executive actions, and government policies to determine their consistency with the Constitution. When applied to legislation, this means that any act passed by Congress can be challenged in court and potentially struck down if it exceeds constitutional boundaries. The Supreme Court, as the highest judicial body, holds the final say in interpreting the Constitution and assessing the legality of federal and state laws.

This power ensures that even democratically enacted legislation must conform to higher constitutional principles. For example, a law that infringes on free speech or equal protection may be invalidated, regardless of its popularity or legislative intent. Judicial review thus acts as a critical check, preventing Congress from overstepping its enumerated powers or violating fundamental rights. While the legislative branch creates statutes, the judiciary ensures those statutes remain within the framework envisioned by the Constitution’s framers.

The Unwritten Power: How Judicial Review Emerged

Remarkably, the U.S. Constitution does not explicitly grant courts the power of judicial review. Instead, this doctrine emerged through judicial interpretation in one of the most consequential cases in American history: *Marbury v. Madison* (1803). At the heart of the case was a dispute over judicial appointments made in the final days of John Adams’ presidency. William Marbury, appointed as a justice of the peace, sued when his commission was not delivered by the incoming Jefferson administration.

Chief Justice John Marshall, writing for a unanimous Supreme Court, faced a delicate political challenge. He recognized that ordering the delivery of the commission might be ignored, undermining the Court’s authority. Yet, failing to act could appear weak. Marshall’s solution was brilliant: he ruled that while Marbury had a right to his commission, the law allowing him to bring the case directly to the Supreme Court—the Judiciary Act of 1789—conflicted with Article III of the Constitution, which defines the Court’s original jurisdiction.

By declaring part of a federal statute unconstitutional, Marshall established a precedent that endures today: the judiciary has the duty to interpret the Constitution and nullify laws that violate it. His assertion—“it is emphatically the province and duty of the judicial department to say what the law is”—cemented the Court’s role as the ultimate constitutional arbiter and laid the foundation for modern judicial oversight of legislative power.

Key Examples of Judicial Checks on Legislative Power

While *Marbury v. Madison* established the principle, subsequent rulings have demonstrated its real-world impact. Throughout American history, the Supreme Court has used judicial review to rein in legislative overreach, particularly during periods of rapid policy expansion.

One such period was the New Deal era of the 1930s. In response to the Great Depression, President Franklin D. Roosevelt pushed for sweeping economic reforms. However, the Court struck down major components of his agenda. In *Schechter Poultry Corp. v. United States* (1935), the Court invalidated the National Industrial Recovery Act (NIRA), ruling that Congress had unconstitutionally delegated legislative authority to the executive branch and exceeded its power under the Commerce Clause by regulating intrastate economic activity. Similarly, in *United States v. Butler* (1936), the Agricultural Adjustment Act (AAA) was overturned because its tax-and-subsidy scheme was deemed an impermissible attempt to control agricultural production—a domain reserved to the states.

Decades later, in *United States v. Windsor* (2013), the Court invalidated Section 3 of the Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA), which denied federal benefits to legally married same-sex couples. The majority held that the provision violated the Fifth Amendment’s guarantee of equal liberty under the Due Process Clause. This decision underscored the judiciary’s role in safeguarding civil rights against majoritarian legislation, reaffirming that democratic processes do not justify constitutional violations.

These cases illustrate that judicial review is not a theoretical concept but a living mechanism that actively shapes governance and protects constitutional values.

The Broader Context: Checks and Balances in Action

Judicial review is just one component of a larger system designed to prevent concentration of power. The U.S. government operates on a model of separation of powers, where each branch possesses distinct responsibilities and the ability to constrain the others. This interdependence ensures accountability and guards against tyranny.

While the focus here is on judicial oversight of Congress, the system functions reciprocally. The legislative branch checks the judiciary by confirming or rejecting judicial appointments, initiating impeachment proceedings, and setting the jurisdiction of federal courts. It can also propose constitutional amendments to override judicial rulings. Meanwhile, the executive checks the judiciary through presidential nominations and the power to grant pardons, while the judiciary checks the executive by reviewing the legality of executive orders and administrative actions.

This dynamic equilibrium allows the government to adapt while preserving core constitutional principles. Each branch serves as both a check and a counterbalance, ensuring that no single entity dominates the political landscape.

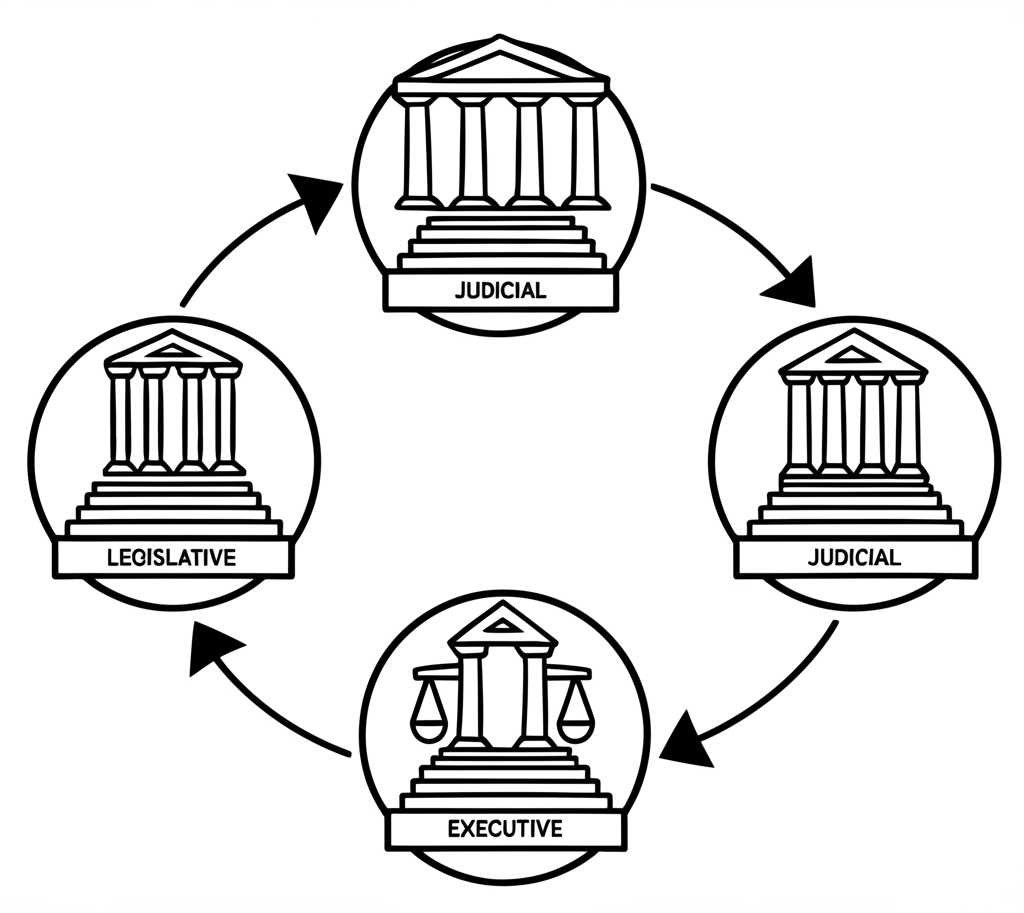

(Image: A diagram illustrating the three branches of the U.S. government and their interconnections through checks and balances, with arrows showing reciprocal oversight.)

Table: Selected Checks and Balances

| Branch | Checks on Legislative Branch (Congress) | Checks on Executive Branch (President) | Checks on Judicial Branch (Courts) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Legislative (Congress) | N/A (Self-checks: internal rules, bicameralism) | Can override vetoes; Impeach President; Approve treaties/appointments; Declare war. | Can impeach judges; Approve judicial appointments; Propose constitutional amendments; Set jurisdiction of courts. |

| Executive (President) | Can veto legislation; Call special sessions of Congress; Recommend legislation. | N/A (Self-checks: internal review, cabinet advice) | Appoints federal judges; Grants pardons. |

| Judicial (Courts) | Can declare laws unconstitutional (Judicial Review). | Can declare executive actions unconstitutional. | N/A (Self-checks: appellate review, stare decisis) |

Impact and Significance of Judicial Review

The long-term influence of judicial review on American law and society is profound. It has served as a stabilizing force, ensuring that legislative action remains grounded in constitutional principles. One of its most vital functions is preserving constitutional limits, preventing Congress from encroaching on powers reserved to the states or the people. This was especially evident during the Civil Rights Movement, when the Supreme Court used judicial review to dismantle state-sanctioned segregation in cases like *Brown v. Board of Education* (1954), overturning laws that violated the Equal Protection Clause.

Moreover, judicial review acts as a shield for minority rights. In a democracy where laws reflect the will of the majority, there is always a risk that marginalized groups may be disadvantaged. The judiciary often serves as their last line of defense, stepping in when legislative bodies fail to uphold constitutional guarantees.

The doctrine also allows the Constitution to remain relevant across changing times. Though the document itself is centuries old, judicial interpretation enables its application to modern issues—from digital privacy to marriage equality. This flexibility, however, sparks ongoing debate. Critics of judicial activism argue that courts sometimes overstep by effectively creating policy from the bench. Supporters counter that judges must interpret the Constitution in light of evolving societal norms. Regardless of perspective, the power of judicial review remains central to the legitimacy and adaptability of the American legal system. For those seeking to understand this principle further, the U.S. Courts website offers authoritative resources on the judiciary’s role in maintaining constitutional balance.

Common Misconceptions About Judicial Power

Despite its importance, judicial review is frequently misunderstood. One common belief is that courts can initiate legal challenges or selectively invalidate laws at will. In reality, federal courts operate under the principle of *case or controversy*—they can only rule on actual disputes brought before them. The judiciary does not issue advisory opinions or conduct preemptive reviews of legislation. A law remains in effect until someone with standing files a lawsuit challenging its constitutionality.

Another misconception is that judges “make law” when they strike down statutes. While judicial decisions can have far-reaching policy effects, the courts do not draft or enact legislation. Their role is interpretive: to apply existing laws and constitutional provisions to specific cases. When a court declares a law unconstitutional, it does not replace it with a new one; it simply removes a legal barrier that conflicts with higher law.

There are also structural limits on judicial power. Congress retains significant influence through its authority to confirm judges, adjust court jurisdictions, and propose constitutional amendments. For instance, after the Supreme Court struck down parts of New Deal legislation, Congress responded by reshaping economic policy and, later, adjusting the Court’s composition. These mechanisms ensure that the judiciary remains accountable within the broader democratic framework. Ultimately, constitutional limits apply to all branches, reinforcing the idea that no institution stands above the Constitution.

Conclusion: Safeguarding Constitutional Governance

Judicial review stands as the judiciary’s most powerful check on legislative authority. Originating in *Marbury v. Madison* and refined through decades of precedent, this doctrine empowers courts to ensure that laws passed by Congress adhere to constitutional principles. It is not a tool for judicial overreach but a necessary safeguard in a system designed to prevent any branch from accumulating excessive power.

By serving as the final interpreter of the Constitution, the Supreme Court plays a crucial role in protecting individual liberties, upholding the separation of powers, and maintaining public trust in the rule of law. Whether invalidating discriminatory statutes or reining in congressional overreach, the judiciary ensures that democratic governance remains bound by constitutional constraints.

This enduring principle continues to shape American life, adapting to new challenges while preserving the foundational values of liberty and justice. For deeper exploration of landmark rulings and oral arguments, the Oyez project provides comprehensive access to Supreme Court cases and historical context.

1. What is the primary way the judicial branch checks the legislative branch?

The primary way the judicial branch checks the legislative branch is through judicial review, which is the power of courts to determine if a law passed by Congress violates the U.S. Constitution.

2. Which landmark Supreme Court case established the power of judicial review?

The landmark Supreme Court case that established the power of judicial review is Marbury v. Madison (1803).

3. Can the judicial branch strike down any law passed by Congress?

The judicial branch can strike down any law passed by Congress only if it is found to be unconstitutional in a case brought before the courts. They do not proactively review all laws.

4. Is judicial review explicitly mentioned in the U.S. Constitution?

No, judicial review is not explicitly mentioned in the U.S. Constitution. It was established through judicial interpretation, specifically in the *Marbury v. Madison* case.

5. What are the broader implications of judicial review for the balance of power?

Judicial review ensures that the legislative branch operates within its constitutional limits, protecting individual rights and reinforcing the separation of powers. It acts as a crucial check to prevent legislative overreach and maintain the balance among the three branches of government.

6. How does the judicial branch’s power differ from the legislative branch’s power?

The legislative branch (Congress) has the power to make laws, while the judicial branch (courts) has the power to interpret laws and the Constitution, and to determine the constitutionality of legislative acts. The judiciary does not create laws but applies and interprets existing ones.

7. What happens if the Supreme Court declares a federal law unconstitutional?

If the Supreme Court declares a federal law unconstitutional, that law is rendered null and void, meaning it cannot be enforced. It effectively ceases to be a valid law.

8. Are there any limits on the judicial branch’s power to check the legislature?

Yes, there are limits. Congress can propose constitutional amendments to effectively overturn Supreme Court decisions, impeach federal judges, and influence the courts’ jurisdiction. Also, judges are appointed by the President and confirmed by the Senate.

9. What is the difference between judicial activism and judicial restraint in the context of legislative checks?

Judicial activism refers to a philosophy where judges are willing to strike down laws and use judicial review to set policy or correct perceived societal wrongs. Judicial restraint, conversely, is a philosophy where judges are more deferential to the legislative and executive branches, typically striking down laws only when they clearly and unambiguously violate the Constitution.

10. Besides judicial review, what are other examples of checks and balances in the U.S. government?

Other examples include:

- The President’s power to veto legislation passed by Congress.

- Congress’s power to override a presidential veto.

- The Senate’s power to approve presidential appointments and treaties.

- Congress’s power to impeach and remove federal officials, including the President and judges.

- The President’s power to appoint federal judges.