Introduction: What is the European Union (EU)?

The European Union, commonly known as the EU, is a groundbreaking alliance of 27 European nations that have chosen to cooperate closely in political, economic, and social matters. Unlike a traditional nation-state or a loose coalition of countries, the EU operates as a hybrid entity—part intergovernmental partnership, part supranational union—where member states retain their independence while sharing authority in specific policy areas. Born from the desire to prevent future conflicts and rebuild a war-torn continent, the EU has grown into one of the most influential regional blocs in the world. Its foundational mission centers on fostering peace, economic integration, and collective well-being, underpinned by the principle of an ever-closer union among European peoples. This framework allows for the free movement of goods, services, capital, and individuals across borders, transforming how Europeans live, work, and trade.

This comprehensive overview explores the essence of the European Union, tracing its historical evolution from post-war reconciliation to a modern political force. We’ll examine its core objectives, the complex network of institutions that govern it, the rigorous process through which countries join, and the tangible impact it has both within Europe and globally. Additionally, we’ll clarify common misunderstandings—particularly the distinction between the EU as a political organization and Europe as a geographical continent—to provide a precise and nuanced understanding of what the EU truly represents.

The Genesis of Integration: A Brief History of the EU

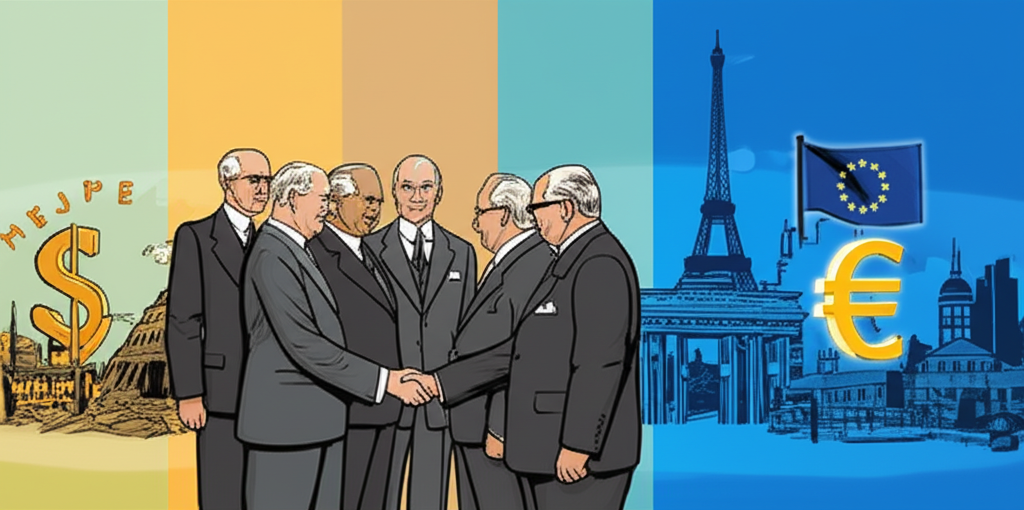

The roots of the European Union stretch back to the aftermath of World War II, a period marked by widespread destruction and a collective determination to prevent future conflicts. European leaders recognized that lasting peace could not rely solely on diplomacy—it required deep economic interdependence. The logic was clear: if nations shared control over vital industries, they would have no incentive to go to war. This vision gave rise to the first concrete steps toward integration, setting the stage for what would eventually become the EU. By binding economies together, European policymakers aimed to create a continent where cooperation replaced confrontation, and prosperity replaced division.

From ECSC to EEC: The Early Years

The catalyst for European unity came on May 9, 1950, with the Schuman Declaration. French Foreign Minister Robert Schuman proposed placing French and West German coal and steel production under a shared authority, open to other European nations. This bold initiative led to the creation of the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC) in 1952, uniting Belgium, France, West Germany, Italy, Luxembourg, and the Netherlands. These six founding members entrusted control of key industrial sectors to a supranational body, marking the first time sovereign states voluntarily pooled authority for mutual benefit.

The success of the ECSC demonstrated that cooperation could yield tangible results, paving the way for broader integration. In 1957, the same six countries signed the Treaties of Rome, establishing two new entities: the European Economic Community (EEC) and the European Atomic Energy Community (Euratom). The EEC, in particular, aimed to create a common market by eliminating tariffs, harmonizing regulations, and enabling the free flow of goods and labor. This represented a significant leap forward—not just in economic terms, but in the political commitment to shared governance and long-term unity.

The Path to Union: Key Treaties and Enlargement Waves

The journey from the EEC to the modern European Union was shaped by a series of pivotal treaties and strategic expansions. Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, the community gradually widened its scope, welcoming new members such as the United Kingdom, Ireland, and Denmark in 1973, followed by Greece, Spain, and Portugal in later decades. At the same time, efforts intensified to deepen integration. The Single European Act of 1986 was instrumental in accelerating the completion of the internal market by setting a deadline of 1992 and introducing mechanisms to streamline decision-making.

A turning point arrived with the Maastricht Treaty, formally known as the Treaty on European Union, which took effect in 1993. This landmark agreement officially established the European Union, transforming the EEC into the European Community and laying the foundation for economic and monetary union—including the introduction of the euro. It also introduced European citizenship, granting individuals rights such as voting in local and European elections in their country of residence. Subsequent reforms, including the Treaty of Amsterdam (1997), the Treaty of Nice (2001), and the Treaty of Lisbon (2009), refined the EU’s institutional structure, enhanced democratic accountability, and adapted its governance to accommodate a growing membership. Over time, waves of enlargement extended the Union eastward, incorporating former Eastern Bloc nations and reinforcing the idea that European integration was both a political and moral project.

Purpose and Core Objectives of the European Union

The European Union is driven by a set of enduring principles and goals, enshrined in its founding treaties and reflected in its daily operations. These objectives are not merely aspirational—they form the legal and policy framework guiding legislation, funding decisions, and international engagement. Designed to improve the lives of EU citizens and project shared values globally, these aims reflect a balance between economic ambition and social responsibility.

Key objectives include:

- Promoting Peace and Stability: To ensure a continent free from armed conflict by fostering dialogue, cooperation, and mutual dependence among member states.

- Establishing a Single Market: To eliminate barriers to trade and movement, enabling businesses to operate across borders and citizens to live, work, and study anywhere within the EU.

- Economic and Social Progress: To promote sustainable economic growth, high employment levels, and strong social protections, contributing to a high standard of living.

- Combating Social Exclusion and Discrimination: To uphold equality and inclusion, addressing poverty and protecting the rights of vulnerable groups.

- Promoting Scientific and Technological Progress: To support research, innovation, and digital transformation through initiatives like Horizon Europe.

- Strengthening Economic, Social and Territorial Cohesion: To reduce disparities between regions through structural funds and investment programs, ensuring balanced development across the Union.

- Respecting Cultural and Linguistic Diversity: To preserve Europe’s rich cultural heritage while fostering mutual understanding and a shared European identity.

- Establishing an Economic and Monetary Union: To coordinate economic policies and maintain financial stability, with the euro serving as the common currency for 20 member states.

- Asserting EU Values on the World Stage: To champion democracy, human rights, the rule of law, and environmental sustainability in global relations and development cooperation.

The Pillars of Power: Key EU Institutions and Their Roles

The European Union functions through a carefully balanced institutional system designed to represent both the collective interest of the Union and the sovereignty of its member states. This structure ensures democratic legitimacy, effective decision-making, and legal consistency across diverse nations. Understanding these institutions is essential to grasping how the EU turns political vision into policy reality.

The European Commission: The EU’s Executive Arm

The European Commission serves as the driving force behind EU policy, acting as the Union’s executive body. It is independent of national governments and tasked with proposing new legislation, managing the EU budget, enforcing EU laws, and representing the EU internationally in certain areas such as trade. Composed of one Commissioner from each of the 27 member states, the Commission is led by a President elected by the European Parliament. It holds the exclusive right to initiate legislation, ensuring that proposals are based on EU-wide interests rather than national agendas. Additionally, it monitors compliance with EU law, initiating legal action when necessary to uphold the integrity of the single market.

The European Parliament: Voice of the Citizens

As the only EU institution directly elected by citizens, the European Parliament embodies democratic representation at the European level. Every five years, over 400 million eligible voters elect Members of the European Parliament (MEPs), who sit in political groups rather than national delegations. The Parliament shares legislative power with the Council of the European Union, meaning most laws require its approval. It also plays a crucial role in supervising the Commission—confirming its composition and holding it accountable through questioning and investigative committees. With full budgetary authority, the Parliament ensures that EU spending aligns with public priorities and values.

The Council of the European Union: Voice of Member States

Commonly referred to as the Council or the Council of Ministers, this institution represents the national governments of the member states. Depending on the topic, different ministers—such as finance, agriculture, or foreign affairs—meet to negotiate and adopt legislation, usually in collaboration with the European Parliament. Decisions are made through a qualified majority voting system or unanimity, depending on the policy area. The Council also coordinates economic policies, defines common positions on foreign affairs, and concludes international agreements. It ensures that national perspectives are integrated into EU decision-making, balancing supranational ambitions with national interests.

The European Council: Strategic Direction

Meeting several times a year, the European Council brings together the heads of state or government of all member states, along with the President of the European Commission and the President of the European Council. While it does not pass laws, it sets the EU’s overall political agenda, addresses crises, and provides strategic guidance on major issues such as enlargement, climate policy, and security. Its conclusions shape the legislative priorities of the Commission and influence the direction of EU integration. The President of the European Council, elected for a renewable two-and-a-half-year term, facilitates consensus and ensures continuity in leadership.

The Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU): Upholding EU Law

Based in Luxembourg, the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) is the guardian of EU law. It ensures that legal interpretations remain consistent across all member states and that EU institutions and national governments comply with treaty obligations. The CJEU hears cases brought by individuals, companies, or governments challenging the legality of EU acts, and it resolves disputes between member states and EU bodies. National courts can also refer questions to the CJEU for preliminary rulings, ensuring that EU law is applied uniformly. Its decisions are binding and have far-reaching implications, from consumer rights to environmental regulations and free movement.

Who Belongs to the EU? Member States and Enlargement

The European Union today is composed of 27 sovereign nations that have voluntarily committed to a shared political and economic project. This membership reflects decades of expansion, from the original six to a diverse community spanning Northern, Southern, Central, and Eastern Europe. Each member state contributes to the EU’s collective strength while benefiting from access to the single market, financial solidarity, and a unified voice in global affairs.

Current Member States of the EU

The EU’s current members are: Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, Czechia, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, and Sweden. This diverse group includes large industrial economies and small island nations, countries with long democratic traditions and those that transitioned to democracy more recently. Despite their differences, all are bound by common treaties, laws, and values.

The Accession Process: How Countries Join the EU

Becoming a member of the European Union is a rigorous and transformative process, designed to ensure that candidate countries are fully prepared to assume the rights and responsibilities of membership. The foundation of this process is the Copenhagen Criteria, established in 1993, which outline three essential requirements:

- Political Criteria: The country must have stable democratic institutions, a functioning rule of law, respect for human rights, and protection for minority groups.

- Economic Criteria: It must operate a viable market economy capable of withstanding competitive pressures within the EU’s single market.

- Administrative and Institutional Capacity: It must be able to effectively implement and enforce EU laws, known as the acquis communautaire, across all policy areas.

The accession process typically begins with a formal application, followed by a screening phase to assess readiness. Once the European Council grants candidate status, negotiations open on 35 policy chapters, which must be closed individually. This phase often involves significant legal and administrative reforms. After negotiations conclude, the accession treaty must be ratified by all existing EU member states and the candidate country, usually through parliamentary approval or referendum. This ensures that enlargement is both thorough and democratically legitimate.

Beyond the Definition: What the EU Does and Its Global Standing

The influence of the European Union extends into nearly every aspect of modern life, from the food on supermarket shelves to the environmental standards that protect communities. Beyond its internal achievements, the EU plays a central role in global diplomacy, trade, and humanitarian efforts, leveraging its size, economic weight, and normative power to shape international norms.

The Single Market and the Eurozone

The creation of the Single Market stands as one of the EU’s most transformative achievements. It guarantees the free movement of goods, services, capital, and people—often referred to as the “four freedoms.” This integration allows businesses to scale across borders, consumers to benefit from greater choice and competitive prices, and individuals to live and work anywhere in the EU without restriction. Supporting this is the Eurozone, which unites 20 EU countries using the euro as their official currency. Managed by the European Central Bank, the euro simplifies cross-border trade, reduces exchange rate uncertainty, and strengthens financial stability. While not all EU members use the euro, participation is a key milestone for deeper economic integration.

The EU’s Role on the World Stage

As a leading global actor, the EU wields considerable influence through diplomacy, trade policy, and development cooperation. It is the world’s largest single market and a top provider of foreign aid, channeling billions annually to support humanitarian relief, democratic governance, and sustainable development. Through the Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP), the EU coordinates member states’ foreign policy positions, deploys peacekeeping missions, and engages in conflict prevention and mediation. It champions multilateralism, actively participating in organizations like the United Nations, the World Trade Organization, and the Paris Climate Agreement. In recent years, the EU has strengthened its strategic autonomy, responding to global challenges such as climate change, digital transformation, and geopolitical instability with coordinated action.

Common Misconceptions: Differentiating the EU from Europe

Despite its visibility, the European Union is frequently misunderstood, particularly in how it relates to the broader continent. Clarifying these distinctions is key to avoiding confusion and fostering informed discussion.

Is the EU a Country?

No, the European Union is not a country. It is a unique political and economic union in which sovereign nations collaborate under shared rules and institutions. While the EU can negotiate international agreements and enact binding legislation, it does not possess the full attributes of a nation-state. There is no single EU army, no unified tax system, and foreign policy remains largely under national control, though coordinated through the CFSP. Decision-making requires consensus or qualified majority support among member states, reflecting the delicate balance between integration and national sovereignty.

The EU vs. Europe: A Clear Distinction

It’s important to distinguish between “Europe” as a geographical and cultural region and the “European Union” as a political entity. Europe is home to approximately 50 countries, many of which—such as Switzerland, Norway, Iceland, and the United Kingdom—are not EU members. Conversely, some EU countries, like Cyprus and Malta, are geographically located outside the continental landmass but are deeply integrated into the European political and economic framework. The EU represents a specific project of integration, not the entirety of the continent. Understanding this difference helps clarify debates about membership, sovereignty, and Europe’s future.

Conclusion: The Evolving Definition of the European Union

The European Union is a living institution, continuously adapting to new challenges and opportunities. From its origins in post-war reconciliation to its current role as a global leader in regulation, trade, and climate action, the EU embodies a bold experiment in cross-border cooperation. It defies simple classification—a union that is neither a federation nor a mere alliance, but a distinctive model of governance built on shared rules, mutual accountability, and a commitment to peace and prosperity.

Today, the EU faces complex dynamics: the aftermath of Brexit, rising populism, migration pressures, and the urgent need to address climate change and digital transformation. Yet, its foundational values—democracy, human dignity, and the rule of law—remain central. As enlargement continues and the Union rethinks its strategic role in a shifting world order, the EU’s ability to evolve while maintaining cohesion will determine its long-term relevance. More than just a political project, the EU is a testament to the possibility of unity in diversity, demonstrating that even in times of division, cooperation can forge a stronger, more resilient future.

1. What is the fundamental meaning of the European Union (EU) and its primary purpose?

The European Union (EU) is a unique political and economic union of 27 member states, primarily located in Europe. Its primary purpose is to promote peace, establish a single market, foster economic and social progress, combat social exclusion, and strengthen economic, social, and territorial cohesion among its members.

2. How many countries are currently members of the EU, and what are the criteria for joining?

Currently, there are 27 member states in the EU. The criteria for joining are known as the Copenhagen Criteria, which include:

- Political Criteria: Stable institutions guaranteeing democracy, the rule of law, human rights, and protection of minorities.

- Economic Criteria: A functioning market economy and the capacity to cope with competitive pressure.

- Administrative and Institutional Capacity: The ability to take on and implement effectively the obligations of membership.

3. What is the historical background of the European Union, including its predecessor organizations?

The EU’s origins trace back to the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC) in 1952, formed to prevent future conflicts. This evolved into the European Economic Community (EEC) in 1957, focusing on a common market. The European Union was officially established with the Maastricht Treaty in 1992, building upon these earlier communities.

4. What are the main institutions of the EU, such as the European Parliament and Commission, and what roles do they play?

The main EU institutions include:

- European Commission: The executive arm, proposing laws and managing the budget.

- European Parliament: Directly elected by citizens, sharing legislative power and supervising the Commission.

- Council of the European Union: Represents national governments, sharing legislative power with Parliament.

- European Council: Defines the EU’s general political direction and priorities (heads of state/government).

- Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU): Ensures EU law is interpreted and applied uniformly.

5. How does the European Union differ from the geographical continent of Europe?

The continent of Europe is a geographical landmass comprising around 50 countries. The European Union, however, is a specific political and economic organization made up of 27 member states within that continent. Not all European countries are in the EU, and the EU is a distinct legal and political entity, not a geographical area.

6. Does the United States or any non-European country belong to the EU?

No, the European Union is specifically a union of European countries. The United States and other non-European countries are not eligible for membership, nor are any currently members.

7. What is the significance of the single market and the Eurozone within the EU?

The Single Market guarantees the free movement of goods, services, capital, and people across member states, fostering economic growth. The Eurozone comprises EU countries that have adopted the euro as their common currency, facilitating trade and investment and promoting economic stability within that area.

8. What are some of the key laws and treaties that govern the European Union?

Key treaties include the Treaty of Rome (1957, establishing the EEC), the Single European Act (1986, completing the single market), the Maastricht Treaty (1992, officially creating the EU and laying groundwork for the euro), and the Treaty of Lisbon (2009, reforming EU institutions and decision-making).

9. What impact does the EU have on the daily lives of its citizens and on global politics?

For its citizens, the EU impacts daily life through consumer protection, environmental standards, free movement rights, common product safety rules, and the single currency. Globally, the EU is a major player in international trade, diplomacy, and humanitarian aid, advocating for multilateralism, human rights, and sustainable development.

10. What is the latest country to join the European Union, and are there any current candidate countries?

The latest country to join the European Union was Croatia, which became a member on July 1, 2013. As of late 2023/early 2024, there are several countries with candidate status, including Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Moldova, Montenegro, North Macedonia, Serbia, Türkiye, and Ukraine, each at different stages of the accession process.