Introduction: What Exactly is the Cash Market?

At the heart of global finance lies the cash market—a dynamic arena where assets change hands with speed and clarity. Often used interchangeably with the term “spot market,” this environment is defined by one central principle: immediate exchange. When a trade occurs here, the buyer pays and the seller delivers, usually within a day or two of the transaction. Settlement timelines like T+0, T+1, or most commonly T+2 govern the process, ensuring that ownership transfers swiftly and transparently. Unlike futures or derivatives, which deal in future obligations, the cash market revolves around present value and real-time possession. It’s where investors gain direct exposure to equities, bonds, commodities, and currencies—making it not only a hub for trading but also the foundational benchmark for pricing across financial systems worldwide.

Core Characteristics and Guiding Principles of the Cash Market

What sets the cash market apart from other financial domains are its core operational traits—elements that ensure efficiency, fairness, and reliability in every transaction. These principles don’t just shape how trades happen; they influence how prices form and how confidence is maintained across markets.

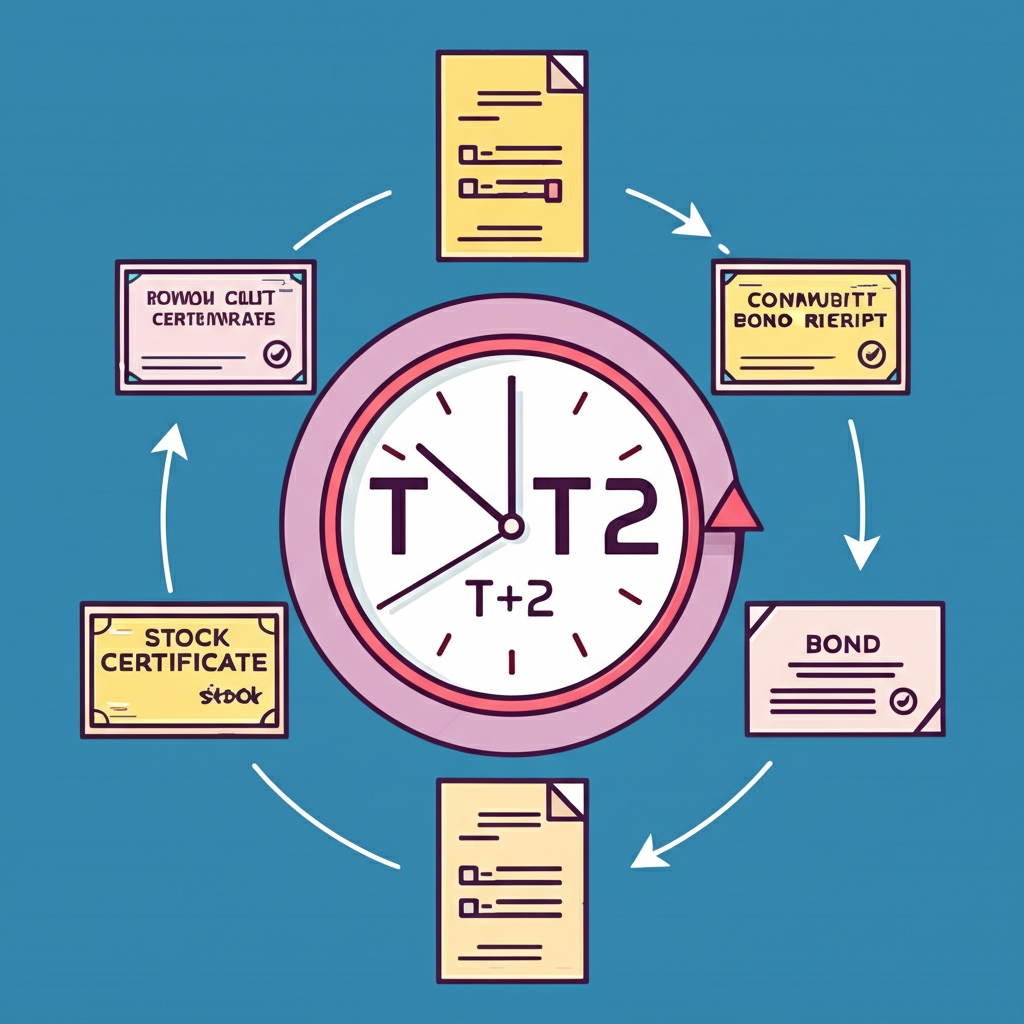

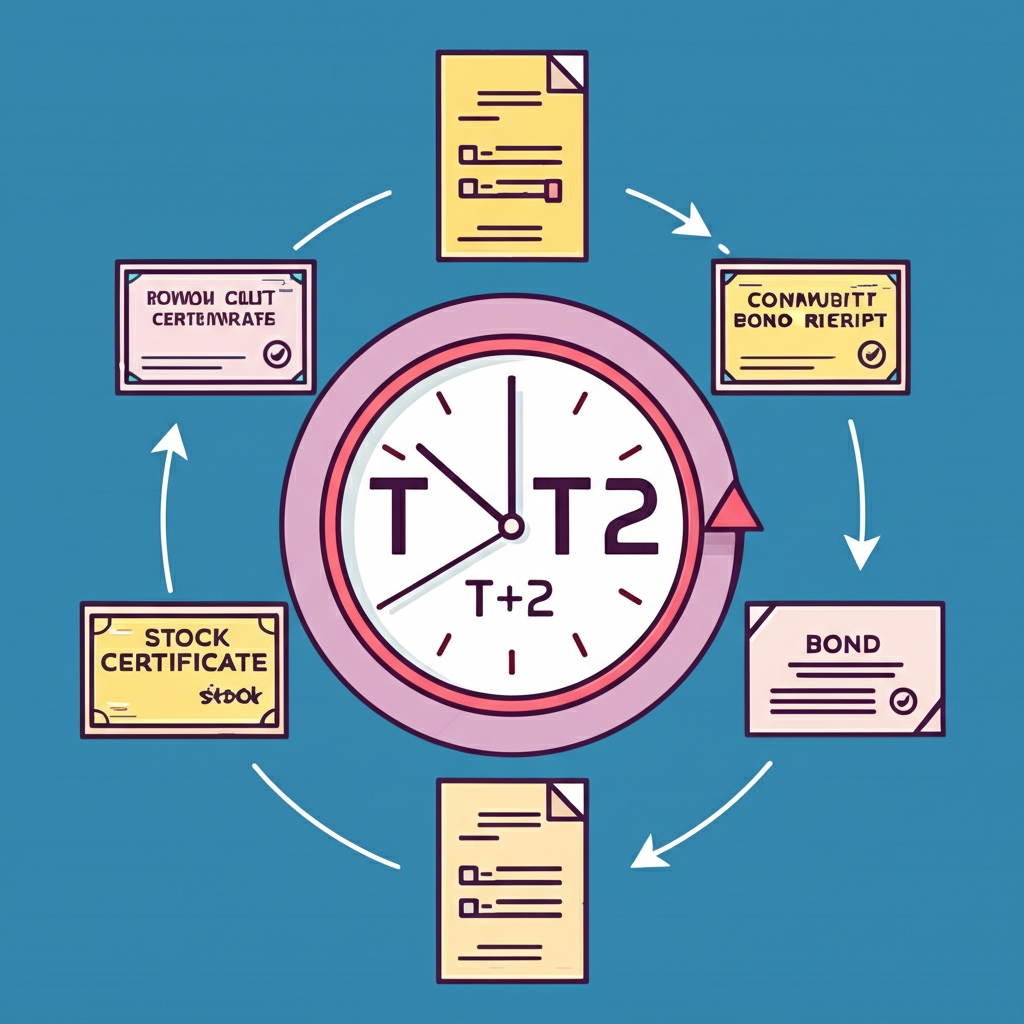

Immediate Settlement and Delivery

The hallmark of any cash market transaction is its emphasis on prompt settlement and delivery. In stock trading, for example, the standard settlement cycle is T+2—meaning two business days after the trade date, funds and shares officially exchange hands. Foreign exchange and some commodities may settle even faster, sometimes on the same day (T+0). Delivery isn’t just a formality—it signifies actual transfer of ownership. Whether it’s shares appearing in a brokerage account, a bond title moving between custodians, or a warehouse receipt changing hands in a commodity deal, the result is real control over the asset. This immediacy reduces counterparty risk and reinforces trust in the system.

Spot Price Determination

Prices in the cash market are known as spot prices—live reflections of what an asset is worth at any given moment. These values emerge purely from the interplay of supply and demand. No future projections are baked in; instead, every fluctuation responds to current conditions. A surprise earnings report, geopolitical tension, shifts in interest rates, or even changes in weather affecting crop yields can instantly reshape valuations. Because these prices are formed in real time and widely disseminated, they serve as critical reference points not only for traders but also for pricing complex instruments like options and futures.

Transparency and Liquidity

One of the cash market’s greatest strengths is its transparency. On regulated exchanges, trade data—including volume, price, and timing—is publicly accessible, allowing all participants to operate with equal access to information. This openness fosters liquidity, especially in major markets like the New York Stock Exchange or the global forex market. High liquidity means investors can enter or exit positions quickly without causing drastic price swings. For institutions managing large portfolios and individual traders alike, this ensures efficiency and reduces slippage during execution.

Standardized vs. Non-Standardized

While standardization enhances efficiency, not all cash markets function the same way. On stock exchanges, every share of a company is identical, enabling seamless trading. Bond markets, however, can vary—especially in over-the-counter (OTC) segments—where deals may be customized in terms of yield, maturity, or terms. Similarly, commodity trades might involve specific grades or delivery locations. Despite these differences, the underlying principle remains unchanged: once a deal is struck, the asset must be delivered and paid for within a short timeframe. This consistency ensures that even non-standard agreements still adhere to the market’s foundational rhythm.

How the Cash Market Operates: Mechanics and Participants

Behind the scenes, the cash market functions through a well-coordinated system of order matching, clearing, and settlement. Its design prioritizes speed and accuracy, enabling millions of transactions daily across diverse asset classes.

The Trading Process

The process begins when a buyer submits a bid and a seller places an ask. Trading platforms—whether electronic or floor-based—match these orders based on price and volume. Once matched, the trade is executed at the prevailing spot price. After execution comes settlement: the buyer’s account is debited, the seller receives payment, and ownership of the asset is formally transferred. This entire sequence, though often completed in seconds electronically, culminates in a legally binding exchange that typically finalizes within one to two business days.

Key Market Participants

A wide array of players contributes to the vitality of the cash market. Individual investors buy stocks or ETFs to build wealth over time. Institutional traders—including mutual funds, pension funds, and hedge funds—execute high-volume trades that shape market trends. Corporations participate by issuing new shares or buying back existing ones, while governments sell bonds to finance public spending. Each group brings different objectives and time horizons, collectively driving market depth and resilience.

Role of Exchanges and Brokers

Exchanges such as the NASDAQ, London Stock Exchange, or Tokyo Stock Exchange provide the infrastructure for fair and orderly trading. They enforce rules, publish real-time data, and oversee the clearing process to maintain integrity. Brokers, meanwhile, act as gateways for most investors. Whether full-service or discount, they execute trades on behalf of clients, offer research, and help navigate regulatory requirements. Without this intermediary layer, access to major markets would be far more limited, particularly for retail participants.

Illustrative Examples of Cash Markets Across Asset Classes

The principles of the cash market apply universally, yet each asset class expresses them in distinct ways. From equities to forex, the core idea of immediate settlement remains consistent.

Stock Market (Equities)

The equity market is perhaps the most familiar form of cash trading. When you purchase shares of a public company like Microsoft or Tesla, you become a partial owner. The transaction settles within T+2, and the shares appear in your brokerage account. This direct ownership entitles you to dividends, voting rights, and exposure to price movements. For long-term investors, this market offers growth potential; for traders, it provides opportunities through volatility.

Bond Market (Fixed Income)

In the bond market, governments and corporations raise capital by issuing debt securities. When an investor buys a U.S. Treasury note or a corporate bond in the cash market, they immediately assume the rights to interest payments and principal repayment at maturity. Settlement typically follows T+2, and ownership is recorded electronically through clearing systems like DTCC. These instruments are vital for portfolio diversification, offering income and relative stability compared to equities.

Commodity Market

Physical goods like crude oil, gold, wheat, or natural gas are actively traded in the cash commodity market. A manufacturer might buy industrial metals today to fulfill a production schedule, paying the spot price for immediate delivery. While physical transfer does occur—especially in energy or agriculture—many transactions involve warehouse receipts or bills of lading that represent ownership. These documents can be traded like securities, allowing businesses to manage supply chains efficiently without moving cargo repeatedly.

Foreign Exchange (Forex) Spot Market

The forex spot market is the largest and most liquid financial market globally. Here, currencies are exchanged at current rates, with settlement usually occurring in two business days (T+2). Multinational companies use this market to pay overseas suppliers, while travelers and investors convert currencies based on real-time exchange rates. The sheer volume and continuous operation—from Tokyo to New York—make it a cornerstone of international trade and finance.

Cash Market vs. Other Financial Markets: Key Distinctions

Understanding the cash market’s role requires contrasting it with alternative financial ecosystems—particularly those involving future commitments or indirect exposure.

Cash Market vs. Futures Market

The futures market operates on a fundamentally different timeline. While the cash market deals in “here and now,” futures contracts bind parties to buy or sell an asset at a set price on a future date. This deferred settlement allows for hedging and speculation without immediate ownership. For instance, an airline might lock in jet fuel prices months in advance using futures, protecting against inflation. But unlike the cash market, most futures positions are closed out before delivery, making them more about price management than actual possession.

| Feature | Cash Market | Futures Market |

|---|---|---|

| **Transaction Type** | Immediate purchase/sale of actual assets | Agreement to buy/sell assets at a future date |

| **Settlement** | Immediate (T+0, T+1, T+2) | Deferred (on a specified future date) |

| **Price Basis** | Spot price (current market value) | Future price (negotiated for future delivery) |

| **Delivery** | Physical delivery or ownership transfer | Can be physical or cash-settled |

| **Leverage** | Typically less direct leverage (margin for buying on credit) | High leverage possible (small margin controls large contract value) |

| **Primary Use** | Investment, consumption, immediate asset acquisition | Hedging, speculation, price discovery |

| **Risk Profile** | Direct exposure to asset price fluctuations | Higher risk due to leverage and potential for margin calls |

As highlighted by Investopedia, futures contracts involve agreements made today for a transaction that will occur in the future, providing a stark contrast to the immediacy of the cash market (Investopedia: Futures Contract).

Cash Market vs. Derivatives Market

The derivatives market includes futures, options, swaps, and other instruments whose value is derived from an underlying asset. In the cash market, you own the asset itself—buying Apple stock means you hold equity in the company. In the derivatives market, you trade a contract tied to that stock. For example, a call option gives you the right—but not the obligation—to buy shares at a set price later. These tools are powerful for managing risk or amplifying returns, but they introduce complexity and often rely on the cash market for valuation and settlement.

Cash Market vs. Spot Market

Though terminology varies, “cash market” and “spot market” refer to the same concept: immediate exchange at current prices. The term “spot market” is more commonly used in commodity and foreign exchange contexts, emphasizing the “on-the-spot” nature of the deal. For example, when a bank trades euros for dollars at today’s rate, it’s operating in the forex spot market—the very definition of a cash transaction.

Cash Market vs. Money Market: Unpacking the Differences

Despite similar names, the cash market and the money market serve different roles in the financial ecosystem. Confusing them is common, but their purposes, instruments, and participant profiles are distinct.

The money market focuses exclusively on short-term debt securities—typically maturing in less than a year. Instruments like Treasury bills, commercial paper, certificates of deposit, and repurchase agreements dominate this space. Its main function is liquidity management: banks use it to meet reserve requirements, corporations fund short-term operations, and investors park idle cash safely.

In contrast, the cash market spans a much broader spectrum. It includes long-term assets like equities and 30-year government bonds, as well as physical commodities and major currencies. While the money market is about safety and temporary deployment of capital, the cash market supports diverse goals—from long-term wealth building to active trading.

Another key difference lies in risk. Money market instruments are generally low-risk due to short maturities and high credit quality. Cash market assets, however, range from ultra-safe (like U.S. Treasuries) to highly volatile (like tech stocks or crude oil). This makes the cash market more versatile but also more exposed to market swings.

The Federal Reserve frequently intervenes in the money market to influence short-term interest rates and manage monetary policy (Federal Reserve: Monetary Policy), underscoring its role in macroeconomic stability.

Navigating the Cash Market: Basic Strategies and Considerations for Investors

Entering the cash market requires more than just placing an order—it demands strategy, discipline, and awareness of market dynamics. Whether investing or trading, understanding your approach and managing risk is essential.

Investment vs. Trading Approaches

Two primary paths define activity in the cash market. Long-term investing involves buying quality assets—such as blue-chip stocks or investment-grade bonds—and holding them for years. The goal is to benefit from compounding returns, dividends, and economic growth. This approach favors patience and fundamental analysis.

On the other hand, short-term trading seeks to profit from price movements over days, hours, or even minutes. Day traders and swing traders use technical signals, news events, and momentum to enter and exit positions quickly. While potentially lucrative, this method carries higher stress and risk, especially during volatile periods.

Analytical Frameworks

Traders and investors rely on two main analytical methods to guide decisions. Fundamental analysis digs into the intrinsic value of an asset. For stocks, this means evaluating earnings, revenue, competitive position, and macroeconomic factors. For commodities, analysts study supply chains, inventories, weather patterns, and global demand.

Technical analysis, meanwhile, focuses on historical price and volume data. By identifying patterns—such as support/resistance levels, moving averages, or chart formations—practitioners attempt to forecast future movements. While often criticized for being subjective, technical tools are widely used, especially in fast-moving markets like forex and equities.

Many successful market participants combine both approaches, using fundamentals to select assets and technicals to time entries and exits.

Risk Management Fundamentals

No strategy succeeds without proper risk control. Even in a transparent and liquid environment, losses can mount quickly without safeguards. Position sizing ensures that no single trade jeopardizes a large portion of capital—common advice suggests risking no more than 1–2% per position.

Stop-loss orders automatically sell an asset when it hits a predefined price, helping to limit downside. Diversification spreads investments across asset classes, sectors, and geographies, reducing reliance on any one outcome. Together, these tools form the backbone of disciplined investing.

Impact of Liquidity and Volatility

Liquidity determines how easily you can trade without moving the market. Highly liquid assets like S&P 500 stocks or major currency pairs allow large orders with minimal slippage. Illiquid assets, such as small-cap stocks or niche commodities, may be harder to buy or sell quickly.

Volatility reflects how much prices swing over time. High volatility can create profit opportunities but also increases uncertainty. Assets like cryptocurrencies or emerging market stocks often attract traders seeking movement, but they require tighter risk controls. Understanding your risk tolerance and aligning it with market conditions is key to sustainable participation.

Conclusion: The Enduring Significance of the Cash Market

The cash market remains the cornerstone of modern finance—a space where real assets meet real buyers and sellers in real time. Its mechanisms—immediate settlement, direct ownership, and transparent pricing—provide stability and clarity in an otherwise complex financial world. From stock exchanges to commodity pits and digital forex platforms, this market enables everything from retirement investing to global trade.

It also serves as the pricing engine for the broader financial system. Futures, options, and other derivatives derive their value from spot prices established in the cash market. Even in an age of algorithmic trading and synthetic instruments, the tangible nature of cash market transactions ensures their continued relevance.

For individual investors, institutions, and corporations alike, the ability to buy, sell, and own assets directly is irreplaceable. As long as economies grow and capital flows, the cash market will remain a vital conduit for wealth creation and economic activity.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What exactly does “cash market definition” mean in finance?

The cash market definition refers to a financial market where assets (like stocks, bonds, commodities, or currencies) are traded for immediate delivery and settlement at the current market price, known as the spot price. It emphasizes the direct transfer of ownership shortly after the transaction.

How does the cash market fundamentally differ from the futures market?

The key difference lies in settlement and obligation. The cash market involves immediate delivery and payment for the actual underlying asset. The futures market, conversely, trades contracts that obligate parties to buy or sell an asset at a predetermined price on a specific future date. Futures involve deferred settlement and are often used for hedging or speculation rather than immediate ownership transfer.

What are some common examples of assets that are typically traded in the cash market?

Common examples include:

- Stocks (Equities): Buying shares of a company on a stock exchange.

- Bonds (Fixed Income): Trading government or corporate debt securities.

- Commodities: Purchasing physical gold, oil, or agricultural products.

- Foreign Exchange (Forex) Spot Market: Exchanging one currency for another at the current rate.

Is the spot market precisely the same concept as the cash market?

Yes, the terms “cash market” and “spot market” are largely synonymous and used interchangeably. Both refer to transactions where assets are bought or sold for immediate settlement and delivery at the current market price (the spot price).

What are the primary characteristics that define a cash market transaction?

The primary characteristics are:

- Immediate Settlement and Delivery: Transactions are completed quickly (e.g., T+0, T+2).

- Spot Price Determination: Prices are based on current supply and demand.

- Direct Ownership Transfer: The buyer immediately gains ownership of the underlying asset.

- Transparency and Liquidity: Often characterized by clear pricing and ease of trading.

How does the settlement process work in the cash market after a trade is executed?

After a trade is executed, the settlement process begins, which is the official completion of the transaction. For stocks, this typically means the cash is debited from the buyer’s account and credited to the seller’s, and the shares are transferred to the buyer’s account, usually within two business days (T+2). The exact timeframe can vary by asset classes and market rules.

What is a basic cash market strategy, and how can individual investors participate?

A basic cash market strategy could involve buying shares of a company with strong fundamentals for long-term investment, aiming for capital appreciation and dividends. Individual investors can participate by opening a brokerage account, funding it, and then placing buy or sell orders for desired assets through their broker or online platform. It’s crucial to conduct thorough research and understand risk management.

Can you explain the key differences between the cash market and the money market?

The cash market trades a broad range of asset classes (stocks, bonds, commodities, forex) for immediate ownership. The money market, on the other hand, specializes in short-term, highly liquid, low-risk debt instruments (like T-bills, commercial paper) used primarily for managing liquidity and short-term funding. Their objectives, instruments, and typical time horizons for investment differ significantly.

Are there any specific risks or advantages associated with trading in the cash market?

Advantages: Direct ownership, transparency, generally high liquidity, and potential for capital gains or income. Risks: Market volatility, price fluctuations can lead to losses, the need for substantial capital (compared to leveraged derivatives markets), and specific risks associated with each asset classes (e.g., company-specific risk for stocks).

Who are the typical participants, and what roles do they play in a cash market?

Typical market participants include:

- Individual Investors: Buy/sell assets for personal portfolios.

- Institutional Investors: Manage large pools of capital (e.g., mutual funds, pension funds).

- Corporations: Raise capital or manage treasury operations.

- Financial Intermediaries: Brokers and banks facilitate trading and provide services.

Each plays a role in contributing to market liquidity and price discovery through their buy and sell activities.